Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

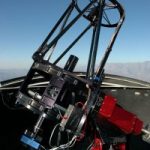

Photo of one of the PROMPT Telescopes. Image credit: Aaron LaCluyze

We’ve explained how to get into astronomy and buy your first telescope. Now we’re going to take things to the next level and get you drooling about bigger and better telescopes. If you’re serious about astronomy, what kinds of telescopes will give you the best bang for big bucks?

|

|

Shownotes

Telescope & Accessories companies:

Telescopes

- Refractor telescopes: these are the least expensive, using refracting lenses housed in a long, thin tube mounted on a tripod. Good for viewing the sun, Moon and planets where magnification detail is important but brightness is not.

- Reflector telescopes: these telescopes are larger and use mirrors housed in large tubes; often reflector telescopes use a mount and are great for viewing faint, deep-sky objects like galaxies, star clusters and nebula.

- Compound telescopes: also called cadioptric telescopes, use both refracting lenses and reflecting mirror in their design.

- Difference between reflector and refractor

Types of Telescopes

- Dobsonian Telescopes

- Schmidt Cassegrain Telescopes

- Newtonian Telescopes

- Ritchey-Chretien Telescopes

- Maksutov Telescopes

- Binocular Telescopes

Accessories:

- Cameras

- Filters

- Anti-blooming filters

- Domes:

Share a telescope:

Transcript: Telescopes, the Next Level

Fraser Cain: You’re drooling. I can hear you drooling over the telescopes. [Laughter]

Dr. Pamela Gay: I got sidetracked from pressing record by telescopes.

Fraser: We’ve explained again through astronomy and buy your first telescope. Now we’re going to take things to the next level and get you drooling about bigger and better telescopes. If you’re serious about astronomy what kinds of telescopes would give you the best bang for the big bucks?

When last we saw our telescopes we were trying to be as safe and inexpensive – big bang for the buck. We were suggesting the Galileoscope although we’ve had a bunch of feedback from people that Galileoscopes have been difficult to get with bad customer service.

Pamela: It’s not bad customer service; it is lack of venture capital.

Fraser: Lack of venture capital, lack of stock, lack of everything. The telescope itself is great if you can get your hands on one. That is the problem. Hopefully they’ll have that problem fixed in the next little while.

We’ve also recommended a nice 6-inch Dobsonian or a small inexpensive refractor, some binoculars, a planisphere, hit it with your eyeballs. Now we’re going to take things to the next level.

I think this show is going to be either for people who want to know how far this little hobby [laughter] can go or what will be the next level? If you do have a smaller telescope, you spent a few hundred dollars, you like it, you like that hobby and now you want to take things to the next level.

We’re going to talk about some of the technologies, some of the scopes and kind of push the limits of money and budget. Money is no object in this show. Alright [laughter] let’s draw a line here in the sand. What would you consider sort of a reasonable, inexpensive budget telescope? Where does that stop?

Pamela: There are people like me that anything that you can’t throw in a backpack or easily carry by yourself – that’s where you draw the line.

For me if I can carry it, that’s first tier. Second tier is a cement pier is required. Third tier is a “costs as much as my car”.

Fraser: Sure but you could have a portable telescope that costs thousands and thousands of dollars.

Pamela: Yeah and that’s where I sort of paused.

Fraser: We’re talking I’d say budget-wise?

Pamela: Budget-wise I’d say once you start getting into the multiple thousand dollars you have moved into a new range of commitment. Up to a thousand dollars, it’s a toy.

It’s a really nice toy; it’s an expensive toy but you’re still in the range of “I bought a laptop even though my company provides me one”. Once you start getting into the many thousands of dollars, you’ve changed your lifestyle to accommodate your hobby.

Fraser: You’ve chosen telescopes over trips; telescopes over new cars; telescopes over clothes. [Laughter]

Pamela: Yes, you’re going to work naked on foot because you have a really cool telescope.

Fraser: What are the kinds of structures? What kinds of telescopes exist as we move into those higher ranges?

Pamela: The first major investment that you start finding is the people who buy the twelve inch and the sixteen inch computer-driven telescopes and build some sort of a shelter around them and attach them to computers.

They make it so that you can no longer really look through them without doing surgery.

Fraser: Right but we’re talking about you might go and buy say a Celestron six inch telescope from them and you can cross into the multi-thousand just buying an eight inch, right?

Pamela: Right but you start asking what I can use this telescope to do.

Fraser: I guess the question is what the configuration is? What is the kind of technology that it is?

Pamela: That second tier of telescopes is when you’ve moved past your binoculars and you’ve moved past your Dobsonian telescope. This is where you start buying some sort of typically Cassegrain telescope.

A Schmidt-Cassegrain a Maksutov-Cassegrain are telescopes where the light comes in through the front of the telescope, reflects off of a mirror at the back of the telescope, hits another mirror at the front of the telescope.

The light then comes out through a small hole at the very back of the telescope and either comes into contact with eyepiece or for more serious observers comes into contact with some sort of a digital or film camera – mostly digital nowadays.

Fraser: When I mentioned Celestron, these are these snub-nosed telescopes, right? They look like they’re maybe 12 inches across or 16 inches but they’re also very short.

Pamela: Yes, they fold the light up. A good one is able to allow you to actually start counting the stars in the Milky Way. It will allow you to start seeing beyond the Seven Sisters and seeing dozens and dozens of stars in the Pleiades.

Fraser: Why is that better than the Dobsonian?

Pamela: There are two big differences that you’re dealing with. One is you have this snub-nosed telescope. One of the things that we talk about is the F-ratio. What is the fastness of an exposure time?

If you’re taking two different photos, one on a Newtonian telescope that has a longer focal ratio and one on one the little short-nosed Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes, you can get the same image in much shorter amounts of time with these little snub-nosed telescopes.

The other thing that you’re dealing with is if you’re putting a really heavy camera on the side of a Dobsonian telescope it’s going to want to – under the force of gravity – tip over. You’re adding a lot of torque to this system.

It’s sort of like trying to hold a really heavy book bag with your arm held straight out from your side. It’s a lot of work. It puts stress on the system and starts to bend the system.

With the Schmidt-Cassegrain you instead have the camera at the very back end of the system. You can easily counterbalance it and you’re able to get much more study exposures without having everything twisted all over the place by the force of gravity.

Fraser: Okay, so then what is a Ritchie-Chretien?

Pamela: There are different types of optical systems that use different shapes of mirrors to get the light from the sky down into your camera system. With the Schmidt-Cassegrains you have two mirrors and a corrector lens. You get fairly large fields of view.

With the Ritchie-Chretien you have much smaller fields of view but you also have amazingly flat fields. What I mean by flat field here is the geometric distortions as you move away from the center of the image are very small.

If you were to take a piece of graph paper and image it with a Ritchie-Chretien all the little graph paper boxes would continue to look like squares whereas with other telescopes you start ending up with pincushion distortion and barrel distortion.

Because you don’t have a corrector plate with a Ritchie-Chretien you also have less light lost. Every time light interacts with the surface you lose some of the photons. They reflect off, they scatter off. They just don’t make it all the way down to your camera.

You have fewer surfaces with the Ritchie-Chretien. The reason every telescope isn’t a Ritchie-Chretien is the mirrors are actually really hard to make because they’re parabolic mirrors.

There’s a trade-off in difficulty in making compared to efficiency of the telescope itself. If you have the extra money, the Ritchie-Chretien is always the correct direction to go in my opinion.

Fraser: Then the last technology you mentioned was a Maksutov-Cassegrain [laughter]

Pamela: I’m willing to let you keep trying [laughter]

Fraser: No, your Russian is much better than mine.

Pamela: [Laughter] A Maksutov-Cassegrain telescope. It is very similar to a Schmidt-Cassegrain. It’s just slightly different geometries.

Most people when they’re switching back and forth between these two telescopes will never know the difference. The big difference is when you go from the Ritchie-Chretien to one of the different types of Cassegrain telescopes.

Fraser: I guess one of the other ways to go is just a gigantic Dobsonian telescope. There’s a guy on Hornby Island where I grew up and I was at his house a couple years ago and he has a 21-inch Dobsonian telescope.

It is 15-feet long and you stand on a big stepladder. It’s just a gigantic light bucket. Nothing fancy, no fancy optics, just a gigantic mirror that collects a ton of light.

The bigger your mirror gets the more expensive things get. That’s a way to have an enormous – but there’s no tracking system. If you wanted to look at a galaxy or whatever you had to push the telescope back and forth and lift it up and down to keep it in your field of view.

It was definitely no good for any kind of astrophotography or anything.

Pamela: This is where sometimes it’s not all about the size. It is actually sometimes all about the motors. When you start investing in these really amazing telescopes, there are two different ways to channel your investment. Actually, there are three different ways to channel your investment.

One of them is less useful than the other two. One thing you can do is just get bigger and bigger mirrors. The most cost-effective way to get giant mirrors is to get some of these giant Dobsonian telescopes like your —–11:11 telescope you got to look through.

Another route to go is to get a completely reasonable telescope; one with nice clean optics but nothing over the top. Invest in a really good camera and a really good drive amount.

If you have a rock-solidly mounted telescope, one that you have a small child bouncing up and down as much as their little heart can carry them and the telescope doesn’t move.

If you have that really good mount and a really good drive system on it so that you’re able to sit on one star for ten or twenty minutes without seeing any distortion of that star being round in your resulting images, you can do absolutely amazing things. For me the real direction to move in is to get one of these great drives.

Get a completely run-of-the-mill telescope system, a good solid camera on the back end of it – I particularly like the cameras because they make this very satisfying noise when they read out. It’s a silly reason to like an instrument, I realize that.

Apogee makes great systems as well; they just don’t make them using noises in the middle of the night. There are lots of different directions you can go and there are ameras as well.

Get a nice solid camera, a nice solid optical system and then pour every dime you have into a drive and nice solid steel or cement pier to put that drive on top of.

Fraser: What’s your favorite drive then?

Pamela: I love the Paramount’s, they just go. You can pile all sorts of different stuff onto them because it’s a very creative mounting system. They basically have a big old sheet of metal that you screw your telescope on to. It’s not sexy. It’s a gorgeous system, beautiful red design, lots of elegantly crafted surfaces to mount your telescopes on to.

It’s not what you expect when you think of big sexy observatory. You have plate of metal that you then bolt your telescopes on to. You can get three or four telescopes depending on their size side-by-side all looking at the sky where you can be looking with you eye through one, keep your tracking on.

You can have a tracking camera on one of them and have your big astrophotography camera on one of them. They track beautifully. They’re solid systems.

I’ve talked to people who have stuffed them in cars, lugged them all over the place setting them up and taking them down and they just go. You pay a small fortune for them.

Fraser: We’ll get to cost in a little while. Let’s not talk about that pesky money [laughter] for now. We’ll come back around to that. For now let’s just dream about the gear.

We’ve talked about some configurations of the telescopes, great big dog Dobsonian or a couple of the ways you can go with the Schmidt-Cassegrain. What about refractors?

Pamela: That’s part of the third option where when you’re making the next step. I wouldn’t go quite here yet. You can get absolutely pristine optics systems, gorgeous stunning chromatic refractors that make you feel like you’re flying through the universe as you skip from one object to another.

One of the amazing things with looking through a refractor is you have much higher contrast than you get with a reflecting telescope. That pays off. If you’re trying to do Astro-imaging you get really good results with the Schmidt-Cassegrain.

In my happy little dream world that I don’t live in but would love to, I have a nice Paramount on top of a cement pier someplace that doesn’t move and I have a good solid 16-inch Ritchie-Chrétien telescope mounted on that Paramount with an amazing Tele Vue Telescope as the finder scope. [Laughter] I can just sit and drink in the sky when I want to and also make amazing images when I want to.

Fraser: Right, your multi-thousand telescope just as your finder scope. Okay.

Pamela: Exactly. It’s my happy little dreamland that I don’t live in. I’m allowed to have whatever I want there.

Fraser: That’s what this show is all about. [Laughter] Dream big Pamela. I guess one other route you can go is really cool binoculars.

Pamela: Yes and what’s really cool is there are binocular telescopes out there. They’re really hard to look through if you’re an uncoordinated person like me. Imagine attaching to each eyeball a 15-inch telescope.

Fraser: I guess size-for-size binoculars are such a much better view. There’s just something so rich about seeing things that you just see details when you have both eyeballs going at the same time.

I forget the name of it – and you may notice this as well – if you look at some text across the room that you can’t quite make out with one eye and then switch to your other eye you can’t quite make it out. Yet if you open up both eyes and look at it you can read the text.

Pamela: What’s happening is your brain is basically folding these two images together the same way digitally you might combine two images. It is able to fill in information based on the two images they couldn’t fill in based on just one.

The human brain is an amazing device for co-adding images even though we don’t actually think that we’re doing that. There are defects in our vision. We have floaters. If you look through a pinhole at a really bright light you may be able to see junk floating around inside your eye.

These are dead cells – it is rather gross and we’ll not wander into biology right now. These floaters detract from your view of the sky. By having both eyes available your brain can go “oops, floater here, gonna subtract it and use the part of the image from this other eye over here”.

For reasons that I don’t think anyone can explain other than it’s the brain, when you look at the universe with two eyes instead of one your mind makes things three-dimensional. We aren’t able to get a separation between our two eyes to actually perceive a three-dimensional sky.

Our brain somehow fills in the pieces to give us a perspective that isn’t real but really cool to experience.

Fraser: Yeah and so does that kind of cover all of the high end gear? We’ve got…

Pamela: Giant binoculars.

Fraser: Big Schmidt-Cassegrain, you have giant binoculars. We’ve got really great refractors, super-duper mounts, monster Dobsonians; does that kind of cover the spectrum? Any other directions that a person might look at?

Pamela: I think that is indeed where you go when you’re planning and ready to move into the next level.

Fraser: Now let’s accessorize. [Laughter] We’ve already talked mounts. As you said a mount is half of the telescope. When you’re at that height, looking at that size of a telescope you really need a mount that is going to keep your image perfectly smooth, is going to track and is able to kinda crank that mass.

Pamela: And honestly it’s sometimes two or three times the price of your telescope.

Fraser: Yeah that’s the part that’s going to make people’s jaws drop. Actually I did an article for Wire about two years ago. I was interviewing all these astrophotographers and getting them to give me some prices.

That was it mount to X telescope X. They went on and on about the mount. But let’s accessorize. What about eyepieces?

Pamela: Yes. I hate this I suddenly have no memory for the new Tele Vue series. There’s the standard Nagler that everyone lives by. These are the types of eyepieces that anytime you see all the people who are in the know about eyepieces, their mouth drops open, saliva starts coming out – Naglers are awesome.

As near as I can tell Al Nagler is an optical genius. He has this new strain of eyepieces out that it feels like you’re looking at a hundred and something degree field of view. It’s just like standing out in the sky except you’re looking through eyepieces.

Fraser: Wow.

Pamela: It’s able to essentially, you look at the Pleiades and the Pleiades wrap around and fill your field of view. That’s just pretty amazing. In general everyone needs something of order of a twenty millimeter eyepiece, a forty millimeter eyepiece and if you have good skies, a six millimeter eyepiece.

The millimeter tells you how much magnification it is. Where a six millimeter is huge magnification and forty millimeter is bordering on binocular magnification.

The Tele Vue new series – it came back to me – is the Ethos series so you can basically see about a hundred degree field of view. They’re giant, they’re awesome. Look through one and dream along with us.

Fraser: Right when you say hundred degrees we’re talking about isn’t the moon a half a degree so you would be seeing a hundred moons?

Pamela: Yes imagine going outside and looking and seeing something the size of the Pleiades expanded out to fill that many times the moon across the sky. It’s taking and embedding you in the sky.

Fraser: Right – camera. If you get serious you’re going to want to install some kind of CCD camera on the back end.

Pamela: Right and if you’re doing astrophotography you probably want to get some sort of a high-end antiblooming CCD. This is one that when you look at too bright of an object doesn’t give you the criss-cross pattern.

If you’re doing science you want something that does bloom because you get better data even if you do when you make mistakes get to see them all over your image. A good high quality CCD, an SBIG, an Apogee, a Fingerlakes, any of these read the reviews.

There are some really nice ones out there. Personally I would never buy a color CCD because you get lower resolution when you do that. Get one that simply goes light – no light – and then buy yourself a filter set. Now we’re looking at eyepieces, camera, filter set on top of it.

Fraser: Filters – we haven’t talked about filters. Do you mean solar filters and different color filters?

Pamela: You can get solar filters and the color filters allow you to either make things look as they would appear to human vision. If you’re doing science you can get filters that are identical to the ones in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey or identical to the ones used in the Palomar Survey.

There are all sorts of different sets of filters out there. You can also get very narrow band ones that allow you to see specific oxygen lines, calcium lines and really figure out what is it that makes planetary nebula appear the way they do. What is it that makes star forming regions appear as they do simply by filtering down to certain colors of light that correspond to different atoms?

Fraser: Enclosures.

Pamela: Yes, [laughter] so the best enclosures are just plywood and hinges put together in the most creative ways. This is why I’m laughing. I’ve seen some of the most amazing enclosure that people have just designed to fit their own personal needs. Ones that fit only the observer they were designed to fit basically.

Fraser: Right.

Pamela: Just as you tailor a suit, you can tailor your observing dome to fit you and your chair and let all of you rotate little tiny circles as you look all over the sky. There are also great commercial domes out there.

There are things like the Robodomes for instance. All sorts of different ones – I don’t want to start endorsing domes because I personally a firm believer in Home Depot domes. Go buy plywood, build one around yourself, hope that you spouse comes out and lets you free occasionally.

Build something that fits you and your needs. If it’s just your telescope, basically build a box that flattens out when you want to observe and otherwise completely encloses your telescope. That way you get the best air circulation around your scope and you don’t care if you’re protecting yourself from the elements or not.

If you need to protect yourself then you start building a little bit more robustly.

Fraser: Let’s talk a bit about automation. We’re in the land of computers now so computers are guiding your telescopes. They are tracking.

If you’re doing your astrophotography they’re handling all your exposures. A lot of telescope work now is all being done remotely, even with hobby equipment.

Pamela: That’s right and one of the talks that made me giggle for the sheer joy of what the person had done was this wonderful talk at the American Association of Variable Star Observers.

This very mechanically inclined individual was talking about how he bought an old Queen Anne Victorian – which is what I have – and it needed a roof so he put a telescope in. [Laughter]

He rigged it up so that when it finished doing an observing run it would set off the alarm clock in his bedroom. He’d go down, go to sleep and either when a water sensor went off, or a weather sensor went off or when the observing run was done, it would wake him up and tell him “come do something with me now”.

Then there are also people with fully automated systems that are capable of detecting clouds for themselves. They go to bed having told their telescope: “take twenty of this, thirty of that call me in the morning”.

Their telescope is capable of waking up doing its standards, observing all over the sky, pointing itself, switching out filters, recognizing the conditions and then putting itself to bed in the morning.

Fraser: I’ve talked to amateur astronomers who do their observing from their laptop at their dining room table. They’re connected wirelessly out to the telescope.

Especially if they’re in the High Sierras and it is thirty degrees below zero outside and their telescope is in the most pristine viewing they can hope for they get to stay in the nice warm comforts of the home and their astronomy continues unabated.

Pamela: One of the really amazing things is there’s actually consortiums of amateurs who basically build their facilities at remote sites where there’s the resident of the communal property who is there in case something goes terribly wrong.

You pay him certain – basically the equivalent of your homeowner’s association – but this is your telescope observatorydom association who is out there in case something goes terribly wrong. But other than that, you might be in Indiana logging into New Mexico.

Fraser: You buy a great telescope. You rent space in this observatory as you said in New Mexico, and you control it entirely through the internet from your house.

You may spend months not seeing your telescope in person. Yet it’s your telescope and it’s doing what you want it to look at. Very cool.

Pamela: What’ really cool is – we say that too many times in this episode, I already have – [laughter] can you tell I like this subject? Not everyone can go out and dump $40,000 on buying a telescope. I’m happy my car works.

For people who need more economical options you can buy shares in professional grade telescopes across the planet. There are all sorts of different on-line communities of observers that jointly own networks of telescopes where people come in and it’s kind of like time-share vacation packages except you don’t end up randomly getting taken by strangers giving you free luggage.

These are actually useful time-shares where you have two or three hours a week, two or three hours a night that you’ve paid for. You get the telescope for you to use and you’re not responsible for the equipment.

You’re not responsible for site maintenance. Your fees go to cover all of that. All you have to worry about is “what am I going to look at tonight”?

Fraser: Alright so let’s bring this back now to Earth [laughter] and talk about money. So sixteen inch Schmidt-Cassegrain with a nice mount – what are we looking at there?

Pamela: The telescope with nothing else attached – we’re talking telescope, nothing, nothing else, you’re looking at several thousand dollars.

Fraser: Right, like two to four thousand dollars. This is your entry level nice telescope.

Pamela: Yeah.

Fraser: Then accessories, you’re easily $5,000 with everything.

Pamela: One really, really good eyepiece can cost you over $500.

Fraser: Then your sort of nice Ritchie-Chretien telescope? [Laughter]

Pamela: Nice Ritchie-Chretien, in my perfect little dream world that I will never live in – well I might – in my happy perfect little dream world, a ten inch Ritchie-Chretien costs $10,000.

Fraser: And that’s just a ten inch.

Pamela: Yes, that’s just a ten inch. For a sixteen inch we’re looking at over $40,000. For a twenty inch we’re talking $60,000.

Fraser: Some of the best amateur astrophotographers out there are using that. They’re using twelve to sixteen inch Ritchie-Chretiens.

It’s like a script you follow. Yeah so $30,000 or $60,000 additional accessories that’s sort of the world you’re living in.

Pamela: We haven’t even gotten to the mount which is about $14,500.

Fraser: Right a mount is another $15,000 on top of the $10,000 for your ten inch telescope.

In your entry level, really nice telescope you’re looking at about $25,000 just for telescope and mount and then another whatever, $5,000 for accessories. Not to mention your dome.

Pamela: One of those random figures that sociologists like to kick about because they collect numbers is someone who is serious about a hobby – whether it is scrap booking or telescopes – will over the course of their lifetime spend as much money on their hobby as they will spend on a really nice car.

It’s not unheard of to spend $30,000 on a really nice pickup truck if you’re an equestrian. Heck it’s not unheard of to spend that much on an SUV if you’re a soccer mom.

To then turn around and spend that much money on a hobby, if you have the land, the property, the skies fits with what sociologists say people do when they invest in a hobby.

Fraser: Okay so really if you were really serious, you’re looking at about $30,000 to $50,000 for a really good setup of a telescope.

Pamela: And other than the camera and you’re going to have to upgrade the engine now and then just like you have to tune up your car now and then.

Fraser: How much is a camera?

Pamela: The camera is probably going to be a couple thousand.

Fraser: Okay. So accessories, eyepieces, camera…

Pamela: But your eyepieces if maintained should last decades. Your telescope if maintained should last decades. Your mount is probably going to need its circuit board replaced at some point. It’s a circuit board – they go bad.

The telescope mount itself should again last a decade if not longer. Paramounts haven’t been around long enough for us to know what their life expectancy is. [Laughter]

But we’re looking at something where unlike other hobbies like I have to feed my horse every month. I will over the course of a lifetime spend this much money on my horse. I just spend a hundred dollars a month for the rest of my life.

Fraser: What about a big refractor?

Pamela: A really big refractor, really nice one you’re looking at $6,000 to $10,000.

Fraser: Then what about good binoculars? Double fifteen inch… [laughter]

Pamela: Double fifteen inch telescope.

Fraser: I would like to try that. I would love to give that a shot sometime. [Laughter] That would be neat.

Pamela: That’s a completely different range of concept. When you start looking at normal giant binoculars, you’re looking at a couple thousand dollars.

Fraser: Okay. So, Ritchie-Chretien is the high end. That’s where the big money gets spent.

Pamela: Yeah.

Fraser: Well, keep on drooling.

Pamela: Hey, Christmas is coming.

Fraser: Christmas is coming, yeah. I know what I’m going to give you. [Laughter] Yeah, next year, thanks Pamela.

This transcript is not an exact match to the audio file. It has been edited for clarity. Transcription and editing by Cindy Leonard.